The Curious Case of Henry Molaison

The human brain is one of the most important part of our body and it took millions and millions of years of evolution to achieve this level of perfection. And even after decades of studies, we have only managed to decode a small section of our brain.

In the 21st century, one of the most well established theory about our brain is about the way it stores information i.e the concept of long term memory and short term memory and how our brain stores different informations in different manner. If you don’t know what it is, here is a really good video explaining the same.

The story behind its discovery is very interesting. It all began from a person famously known as Patient HM in the world of neurosciencec. In order to completely understand the story, we need to travel back in time, back to America in the 1950s where our story takes place.

The 20th century

After the world war, there was rapid development in science and technology. But there was one area that was rather crude and not much developed and that is Neuroscience.

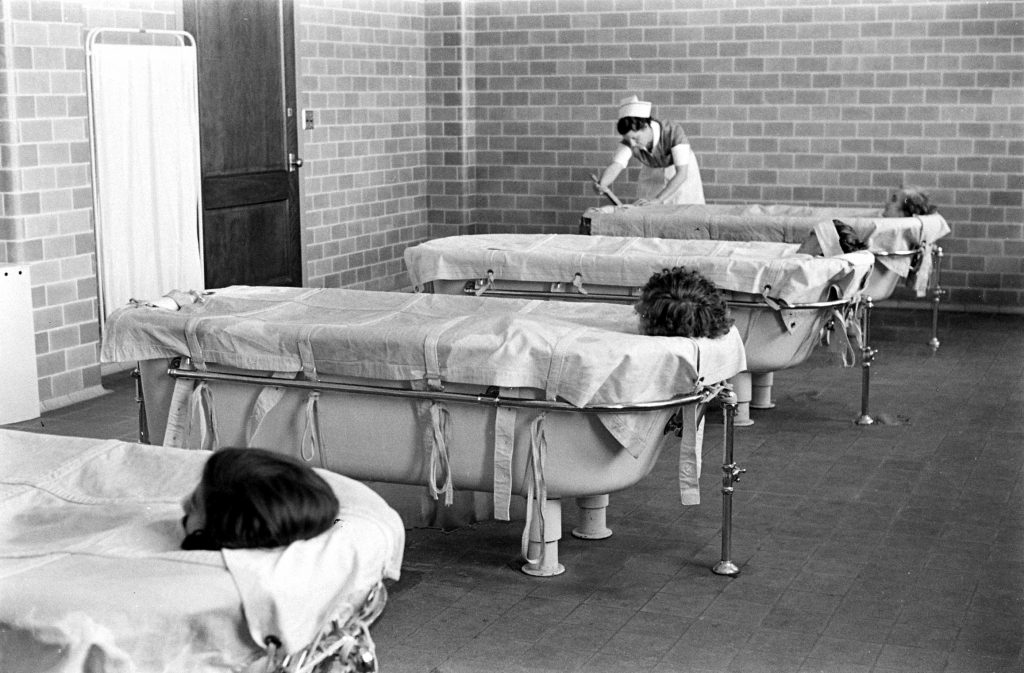

The knowledge about our brain, mental health and other mental illnesses was not that developed and there weren’t any ethical barriers to performing medical procedures. Patients sufferring from mental illness were locked up in what were known as mental asylums. They were experimented on and the treatments at the asylums were completely crazy and irrational. The patients were electrocuted with high voltages applied to their temples. The patients had to undergo regular hydrotherapy, where they were submerged in extremely cold water to calm them down.

We mostly hear about mental asyulms in horror movies, but this was the harsh reality back then. It was a crazy period and there wasn’t much knowledge or awareness about mental health. Then came another revolution in neurosurgery, the Lobotomy.

Lobotomy

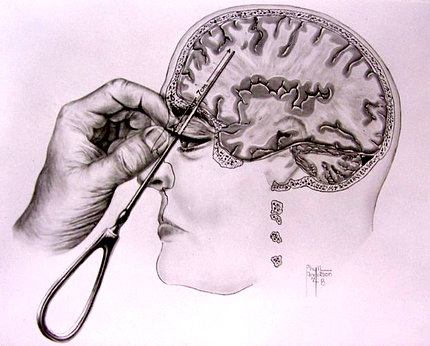

This medical procedure was developed by doctors in Europe. The motto behind lobotomy was that if a certain part of the brain causes problem, just cut it out and everything will be fine. It was thought that cutting certain nerves in brain can fix the excess emotion and stabilize the person. A hole was drilled into the patient’s head from their eyeball socket and and they used to sever brain connections by using knives or by pouring ethanol.

Lobotomy was hailed as an innovation, an instant cure for mental patients. There were more than 50,000 of these surgeries performed just in America. Soldiers suffering from PTSD due to the world war, perform Lobotomy and he’ll be instantly cured. If someone is emotionally unstable, perform lobotmy and they’ll be instantly cured. Of course, in reality, lobotomy was not exactly a cure. It was just cutting open the brain and mushing around with the brain tissues.

“As those who watched the procedure described it, a patient would be rendered unconscious by electroshock. Freeman would then take a sharp ice pick-like instrument, insert it above the patient’s eyeball through the orbit of the eye, into the frontal lobes of the brain, moving the instrument back and forth. Then he would do the same thing on the other side of the face.” -Quoted in the National Public Radio

Did these procedures work? No, definitely not. There were very slim chances of surviving such a procedure. The success rate was less than 50% and even amongst those who survived, the lobotomy had negative effects on a patient’s personality, initiative, inhibitions, empathy and ability to function on their own. Those who survived were left as nothing more than empty shells unable to do anything.

Henry Molaison

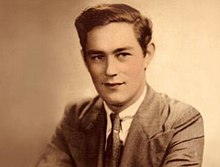

Henry Molaison, popularly known in the world of neuroscience as Patient HM is the foundation for all the knowledge we have about brain. Most of the knowledge that we have about our brain can be traced back to this person.

Henry was born in Connecticut, U.S in 1929. After a bicycle injury at the age of 7, he started suffering from intractable epilepsy. He had minor or partial seizures for many years, and then major or tonic-clonic seizures following his 16th birthday. He used to work on an assembly line but by the age of 27, he had become so incapacitated by his seizures that he could not work nor lead a normal life.

The doctors tried various remedies including high dosages of anticonvulsant medication but none of them yielded good results. Dr Scoville, the then neurosurgeon at the Hartford Hospital in Connecticut, decided to perform a lobotmy. Scoville had localized Molaison’s epilepsy to the left and right medial temporal lobes. On 1st September 1953, Molaison allowed surgeons to remove a thumb-sized section of tissue from each side of his brain. It was an experimental procedure that he and his surgeons hoped would quell the seizures wracking his brain.

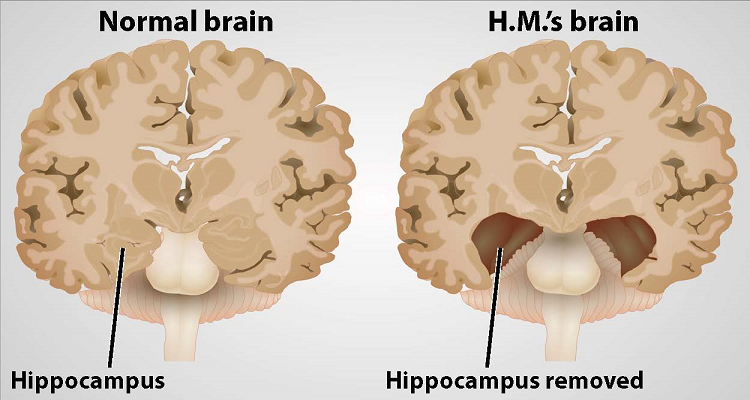

Although there weren’t any strict ethical code for doctors during those times, the lobotomy was said to have been performed with the consent of the patient and his family. Scoville removed Molaison’s medial temporal lobes on both hemispheres including the hippocampus and most of the amygdala and entorhinal cortex, the major sensory input to the hippocampus.

Surprisingly, the surgery was successful. Molaison’s seizure were abated and more controllable. But Scoville didn’t consider the implications of his surgery. Molaison was left with dense memory loss. He suffered from what we now know as retrograde amnesia. Obviously, this was not scientifically established back then in 1950s. Up until then, it had not been known that the hippocampus was even essential for making memories, and that if we lose both of them we will suffer an amnesia. Once this was realized, the findings were widely publicized so that this operation to remove both hippocampi would never be done again.

When Scoville realized his patient had become amnesic, he referred him to the eminent neurosurgeon Dr. Wilder Penfield and neuropsychologist Dr. Brenda Milner of Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI), who assessed him in detail. Penfield and Milner had already been conducting memory experiments on other patients and they quickly realized that Henry’s dense amnesia, his intact intelligence, and the precise neurosurgical lesions made him the perfect experimental subject.

For 55 years, Henry participated in numerous experiments, primarily at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where Professor Suzanne Corkin and her team of neuropsychologists assessed him. He died in December 2008 at the age of 82.

The Research on Molaison

Henry’s memory loss was far from simple. Firstly, he was unable to make any new memories after his operation. He also had moderate retrograde amnesia i.e he could not remember most events in the 1-2 year period prior to his surgery. In some cases, he couldn’t remember events upto 11 years before the time of surgery. He could remember some things — scenes from his childhood, some facts about his parents, and historical events that occurred before his surgery — but he was unable to form new memories. If he met someone who then left the room, within minutes he had no recollection of the person or their meeting. He was perpetually “trapped in the moment,” unable to recall anything beyond 30 seconds.

Scoville and Milner described their findings in their 1957 paper titled “Loss of recent memory after Bilateral Hippocampal Lesions”. They realized that only patients who had specific portions of their medial temporal lobes removed experienced memory problems. And, the more tissue removed, the more severe the memory impairment. The researchers noted patients’ amnesia was “curiously specific to the domain of recent memory.” This led to the understanding that complex functions such as learning and memory are tied to discrete regions of the brain.

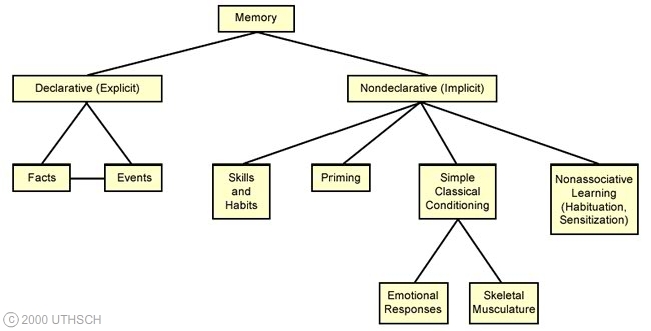

Henry lived for 55 years without acquiring any new declarative memories. His surgery, however, left intact other circuits that supported his nondeclarative memory, so he could learn new motor skills and acquire conditioned responses. He was a very happy and friendly person and always a delight to be with and to assess. He never seemed to get tired of doing what most people would think of as tedious memory tests, because they were always new to him! When he was at MIT, between test sessions he would often sit doing crossword puzzles, and he could do the same ones again and again if the words were erased, as to him it was new each time.

A brief summary of his condition is as follows:

- Henry’s short-term memory was intact; whereas he failed to convert short-term memories into long-term memories

- Forgot new experiences after operation and inability to form new memories

- His semantic memory for prior to operation was intact (recalled historical facts, recognized relatives, good vocabulary) and had intact procedural memory

- The episodic memory prior to operation showed deficits

- His IQ was above average

- His language, reasoning, and perceptual capacities were normal.

The study of Molaison revolutionized the understanding of the organization of human memory. It has provided broad evidence for the rejection of old theories and the formation of new theories on human memory, in particular about its processes and the underlying neural structures. Some of the breakthrough discoveries from his study are as follows:

- Partition of memory into short-term and long-term memory processes, each part being mediated by a specialized memory circuit. It became evident from a series of cognitive tests that short-term memory is the immediate present. Its capacity is limited and fades immediately unless (a) We rehearse it or (b) convert it into a form that can be retained in long-term memory. Henry was able to use rehearsal but unable to convert short-term memories into long-term memories

-

Duration of short-term memory - Henry could easily and accurately perform the task when there was no delay between stimuli, however, the ability to differentiate between stimuli became harder as the gap between them got longer beyond 30s. At 60s, it was just a random performance. The abrupt breakdown in Henry’s performance between 30s and 60s showed that the duration of short-term memory last less than 60 seconds.

-

Concept of semantic and episodic memory as being distinctly organized in brain - In case of Hnery, most details of unique events were lost (episodic, autobiographical memory) but general knowledge of the world is preserved (semantic memory), indicating that the anatomical substrates for these two forms of memory were distinct. We now know that the medial temporal-lobe structures are engaged in the initial encoding, storage, and retrieval of both kinds of memories. Then, during the process of consolidation, semantic memories become permanently established in the cortex while episodic, autobiographical-memory traces continue to depend on medial temporal-lobe structures indefinitely. Thus, the removal of this tissue from Henry’s brain left him devoid of autobiographical memories

-

Henry’s spatial memory-declarative memory for spatial locations was deficient. It established the importance of the hippocampus for spatial learning. However, after a few days, he could accurately draw the map of the house where he lived, means that other brain areas took over the job of encoding and storing that rich spatial information. This task depended on the parahippocampal gyrus, part of which remained in Henry’s brain on both sides. Hence, on rare occasions, he somehow compensated for the devastating effect of his hippocampal damage by mobilizing preserved brain structures and networks.

-

Recognizing that learning can take place without awareness (non-declarative memory) was one of the most significant advances. Henry learnt to use a walker. Dr. Milner introduced the idea that some memory processes were not hippocampus-dependent by showing that Henry’s error scores decreased across 3 days of testing on a motor skill-learning task, that is, mirror tracing. This discovery constituted the first experimental demonstration of preserved learning in amnesia. The “non-declarative memory” typically was not impaired in Henry’s case. Dr. Milner’s view was further strengthened by the touch-guided maze test, which was first demonstration within a single experiment, of impaired declarative learning (failure to learn the correct route) with preserved procedural i.e non-declarative learning.

-

A healthy hippocampus is essential for vividly recounting the details (recollection), but that it is not essential for simply recognizing a face, without identifying it or placing it in a context (familiarity)

-

Henry was able to produce conditioned responses in eye blink conditioning experiment, which helped to speculate that the conditioned memory, which was intact, was not mediated by medial temporal lobe.

-

The brain circuit responsible for odour detection (this bottle contains an odour) and odour intensity discrimination (this odour is stronger) is separate from the circuit that supports odor discrimination (this smells like cloves). Henry could not do latter. We now know that odor discrimination takes place in the front part of the parahippocampal gyrus, the amygdala, and the cortex around the amygdale.

Further Studies

Henry laid the foundation for all the future studies and he was the only patient who was lobotomized. Lobotomy was later banned in the 1970s due to it being “contrary to the principles of humanity”.

Henry was not the only patient who was studied on. In the later decades there were several more patients who were under study for example, Kent Cochrane, who suffered from severe anterograde amnesia due to an accident in 1981. His semantic memory was intact but lacked episodic memory.

Decades after this event. we still haven’t been able to completely grasp the workings of the human brain. But there has been a considerable growth in the amount of knowledge available to use. We are able to treat mental illness that were considered untreatable back in the 20th century. I beleive that in the future, we will be able to completey understand the workings of human brain and even supersede it. We have already been able to build neural networks which are able to identify and classify faces better than humans. We have also managed to build mechanical systems using deep learning that are able to percieve better than humans. There is a lot to look forward to in the future!

References

-

Barbara Dury, Lobotomy: A Dangerous Fad’s Lingering effect on Mental Illness Treatment

https://www.retroreport.org/video/first-do-no-harm/ -

Ben Cosgrove, Strangers to Reason: LIFE Inside a Psychiatric Hospital, 1938

https://www.retroreport.org/video/first-do-no-harm/ -

Tanya Lewis, Lobotomy: Definition, Procedure & History

https://www.livescience.com/42199-lobotomy-definition.html -

National Public Radio, Frequently Asked Questions About Lobotomies

https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5014565&ps=rs -

Jacopo Annese, Natalie M, Hauke Bartsch, Postmortem examination of patient H.M.’s brain based on histological sectioning and digital 3D reconstruction

https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms4122 -

Barbara Dury, Lobotomy: A Dangerous Fad’s Lingering effect on Mental Illness Treatment

https://www.retroreport.org/video/first-do-no-harm/ -

William Scoville, Brenda Miller, Loss of recent memory after Bilateral Hippocampal Lesions

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC497229/ -

Bigya Shah, Raman Deep Pattanayak, Rajesh Sagar, The study of patient henry Molaison and what it taught us over past 50 years: Contributions to neuroscience

https://www.jmhhb.org/article.asp?issn=0971-8990;year=2014;volume=19;issue=2;spage=91;epage=93;aulast=Shah